Anesthesiologists can play a critical role in assessing and reducing the risk of perioperative and acute ischemic stroke in non-cardiac surgery patients through careful screening, managing antithrombotic therapy, and even scheduling optimal timing for elective surgery. Those considerations as well as keeping the anesthesiologist safe during the pandemic were the focus of Saturday’s session, “Stroke and the Anesthesiologist: What’s New?”

Session Moderator Kathryn Rosenblatt, MD, MHS, of Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, led the panel discussion, which featured Laurel E. Moore, MD, of the University of Michigan Medical School in Ann Arbor, and Matthew K. Whalin, MD, PhD, of Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta. The two described the specialty’s practical and evidence-based approach in all phases of care, from the neurointerventional radiology suite to the neurocritical care unit.

Session Moderator Kathryn Rosenblatt, MD, MHS, of Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, led the panel discussion, which featured Laurel E. Moore, MD, of the University of Michigan Medical School in Ann Arbor, and Matthew K. Whalin, MD, PhD, of Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta. The two described the specialty’s practical and evidence-based approach in all phases of care, from the neurointerventional radiology suite to the neurocritical care unit.

“We know patients are aging. And while non-cardiac surgical volumes are constant, the number of patients over the age of 60 and 75 is increasing,” Dr. Moore said. “Clinically recognized stroke is rare – approximately 0.1% for low-risk patients undergoing low-risk procedures. This low incidence and the absence of easily accessed biomarkers makes perioperative stroke difficult to study. Significantly, we may be seeing just the tip of the iceberg.”

In referencing the 2018 NeuroVISION clinical trial, Dr. Moore said that neuropathologic abnormalities were the biggest contributor to the incidence of new covert stroke. According to Dr. Moore, the incidence of new covert stroke is actually 7%, as diagnosed by postoperative MRI in patients 65 and over. Anesthesiologists who understand these complexities can be critical in reducing the incidence, she said.

Proper timing for elective surgeries, for example, can be a significant benefit to patient outcomes, she said. Studies show it may be best to wait nine months after a stroke to undergo an elective surgery.

Similarly, Dr. Whalin discussed the anesthesiologist’s role in endovascular stroke intervention. He highlighted recent studies linking intraprocedure hemodynamic management to patient outcomes after mechanical thrombectomy (MT) and explained the latest data on choice of anesthetic modality for MT.

One 2019 game-changing study of note, he said, underscored the importance of tightly controlling baseline blood pressure rates and hypotension duration from the point of admission.

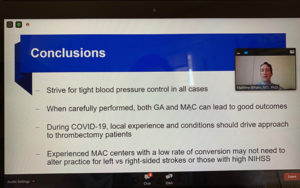

“We are aiming for just the right blood pressure,” he said. “The studies recommend keeping the MAP no less than 10% from baseline and the importance of quickly and aggressively treating high blood pressure, since duration is key.”

According to Dr. Whalen, the latest data on choice of anesthetic modality indicates both general anesthesia and monitored anesthesia care can lead to good outcomes when carefully performed.

In an effort to address patient and provider safety during the COVID-19 pandemic, Dr. Whalen said local experience and conditions should drive anesthesiology’s approach for thrombectomy patients.

For general anesthesia during COVID-19, anesthesiologists should have a multidisciplinary plan for the location of intubation (the emergency department versus the angio suite), manage sedation and blood pressure during transport (if outside the angio suite), monitor air exchange rates if intubating in the angio suite, use viral filters and prevent circuit disconnection, plan the location for extubation, and clarify cleaning protocols for both the angio suite and extubation area.

For monitored anesthesia care, Dr. Whalin said anesthesiologists should consider a patient’s risk and have a plan to convert to general anesthesia if necessary, equip the patient with a surgical mask, and avoid actions that may increase viral spread, such as high-flow supplemental oxygen and manipulation (i.e., airway insertion, jaw thrust, chin lift, etc.). Unfortunately, he said, there is very little COVID-19 data on predictors for conversion.

Return to Index