Careful assessment and planning can help anesthesiologists have strategies in place before the induction of anesthesia, which saves crucial time if an emergency occurs. The international group of experts in Monday’s “Workshop on Management of the Difficult Airway, Including Simulation” focused on the key element of time and the importance of planning carefully for potential emergencies. Workshop participants heard brief, evidence-based overviews on specific aspects of advanced airway management and then practiced in hands-on demonstrations at seven interactive workstations.

“The workshop is based on the scientific literature,” said Elizabeth Behringer, M.D., Professor of Anesthesiology and Critical Care at Cedars Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, and a co-moderator of the workshop. “Guidelines rarely discuss individual devices but rather groups of devices. The workshop addresses specific devices for which there is a body of literature that supports their use. Participants are introduced to the devices in the workshop and can read more about them afterward.”

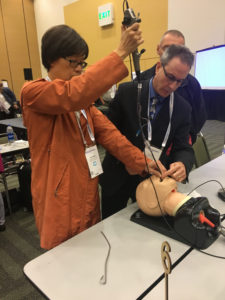

Workshop participants had the opportunity for hands-on demonstrations.

Joseph Quinlan, M.D., Department of Anesthesia and Perioperative Medicine at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center said, “The overall goal of the workshop is to teach anesthesiologists to follow the ASA Difficult Airway Algorithm, from induction to intubation and extubation.”

Workshop participants indicated that difficult mask ventilation is a key safety concern. According to the ASA guidelines, as well as the guidelines of the Difficult Airway Society, when facemask ventilation is inadequate, Plan B is a supraglottic airway device (SAD). Dr. Ellen O’Sullivan, Consultant Anesthetist at St. James’s Hospital, Dublin, Ireland, discussed intubation through a SAD. She said the emphasis should be on oxygenation via a SAD rather than intubation, and second-generation SADs are recommended. “You should not blindly intubate with an LMA,” she said.

Success rates are higher with a fiberoptic scope, and she illustrated a step-by-step approach to fiberoptic-guided tracheal intubation through a SAD using the Aintree intubation catheter (Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN). Dr. O’Sullivan referred to use of the catheter as a “low-skill technique,” but said, “You must practice.”

Richard Cooper, M.D., FRCPC, Professor of Anesthesia at the University of Toronto, discussed first-pass success (FPS), focusing on the patients who benefit the most from FPS and how best to achieve it. He described three risk factors for multiple attempts at intubation: an anatomically difficult airway, a physiologically difficult airway and contextual difficulties.

FPS is important because studies have shown that complication rates are higher when more than one attempt is required. However, Dr. Cooper cautioned against taking too much time in an effort to intubate on the first pass. He said if intubation seems unlikely on the first attempt, steps should be taken to optimize the second attempt. He encouraged attendees to use the device that had the highest potential in their hands.

Attempts at intubation should be limited to allow surgical access to be performed in time for a good outcome. In more than 60 percent of cases in which there was a CICO (can’t intubate, can’t oxygenate) event, a surgical airway was obtained but was too late to avoid a poor outcome, said Paul A. Baker, M.D., M.B., Ch.B., FANZCA, Senior Lecturer, Anesthesiology, School of Medicine at the University of Auckland, New Zealand. Dr. Baker advocated for careful planning by identifying landmarks in patients who are likely to have a difficult airway and using ultrasound early as an aid in identification.

Anesthesiologists should have a standardized plan with a simple technique to help eliminate time needed for decision-making. “You don’t want to debate issues once something happens,” said Dr. Baker.

The most common and most successful approach for front of neck access is scalpel cricothyroidectomy, which can be accomplished with just three pieces of equipment: a scalpel, a bougie and a tube. This method can be done in 36 seconds and is the procedure recommended by the Difficult Airway Society, he said.

Dr. Baker also mentioned The Airway App, which is being used to gather data on the methods used for front of neck access. He encouraged attendees to help contribute to data through the app.

Time is an important element in managing the airway, and preoxygenation is valuable because it extends the length of time of apnea without desaturation. Given this benefit, preoxygenation should be done for every patient, said Anil Patel, M.B., B.S., FRCA, of the Royal National Throat, Nose and Ear Hospital, and University College Hospital, London. Dr. Patel said an important aspect of preoxygenation is the distinction between efficacy and efficiency. Efficacy, he said, refers to maximizing alveolar oxygenation, whereas efficiency refers to prolonging the apnea time after induction of anesthesia. Flushing the anesthesia circuit with high oxygen flow, ensuring a good seal with the face mask, and achieving adequate oxygen flow (tidal volume versus deep breathing) can help improve efficacy. A head-up position, apneic oxygenation with nasal oxygenation during efforts of securing a tube (NODESAT) and apneic ventilation with transnasal humidified rapid insufflation ventilatory exchange (THRIVE) can help enhance efficiency. Dr. Patel also recommended delivering oxygen through a nasal cannula to help increase the apnea time. He said it is necessary to preoxygenate before extubation.

Also important is identification of the cricothyroid membrane, according to Michael S. Kristensen, M.D. from the Department of Anesthesia, Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen. Accurate localization of the cricothyroid membrane is essential for emergency airway access, and the structure should be identified before an emergency occurs.

“Look first – that will often be sufficient. Palpate if necessary, and if still in doubt, supplement with ultrasonography,” Dr. Kristensen said.

Studies have shown that ultrasound-guided identification of the cricothyroid membrane is more successful than palpation, which has led to its increasing use, he said. Other indications for ultrasound of the airway are to identify tracheal rings for ultrasound-guided tracheostomy and to confirm tracheal or esophageal intubation.

Ultrasound also can be used to assess gastric contents, providing information on the risk for aspiration. Its use can determine if the stomach is empty or if it contains solid content or clear fluids. Mathematical calculations can determine the quantity of contents.

“It is especially challenging for anesthesiologists in private practice to learn new techniques and how to use new equipment,” Dr. Behringer said. “Participating in the workshop teaches them how to bring the new techniques and devices into their practice. We are incredibly indebted to the vendors who gave us equipment to use in the workshop. We couldn’t offer this workshop without their support.”

Return to Archive Index